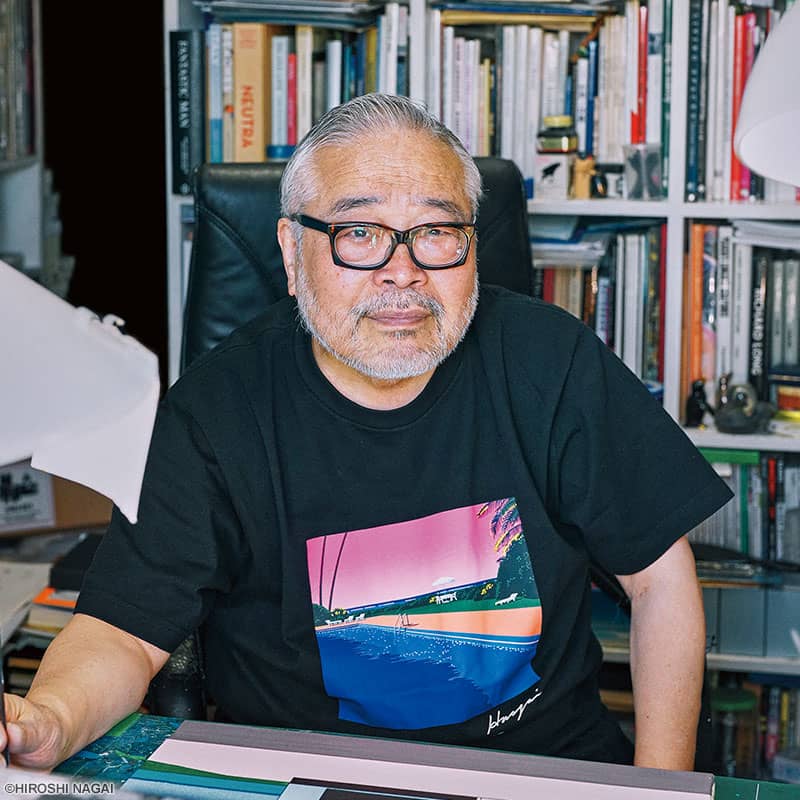

KNOWN FOR HIS RADIANT SKIES, TRANQUIL COASTLINES, AND ENDLESS SUNSETS, HIROSHI NAGAI CAPTURES THE ELUSIVE BEAUTY OF SUMMER LIKE A DREAM THAT NEVER FADES. HIS WORLD TRANSPORTS US TO AN IDEALISED YET DEEPLY FAMILIAR PLACE, A SUN-DRENCHED MOMENT, SILENT AND SUSPENDED BETWEEN NOSTALGIA AND SERENITY.

COMPOSED WITH CINEMATIC PRECISION AND BATHED IN PERFECTLY BALANCED, LUMINOUS COLOURS, HIS SCENES HAVE BECOME TIMELESS ICONS OF JAPANESE POP CULTURE AND COLLECTIVE VISUAL MEMORY.

(Recorded and transcribed by Sayaka Shibata, Tokyo — July 31, 2025)

SS: Your works evoke a timeless summer, almost dreamlike. What does “eternal summer” mean to you personally? And how has this vision changed since the 1980s?

HN: Honestly, it hasn’t changed since the ’80s.

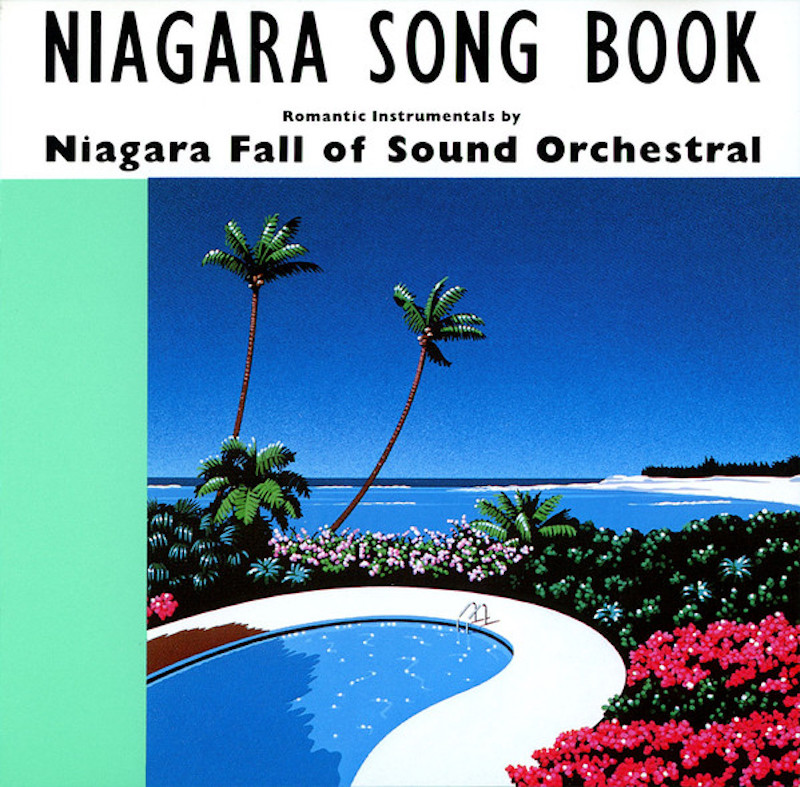

Back in the mid-1970s, I traveled to places like America and Guam. Those experiences of summer stayed with me. In the ’80s, because of commercial shoots, I often went to Hawaii. That’s when I grew to love it — but not so much the actual scenery I saw there. Rather, it was the idea of southern islands and Los Angeles, the way you feel it from Japan. That’s what I painted.

I was never really interested in new landscapes. Even hotels — I preferred the older ones, not the brand-new luxury ones along the beach, but the small hotels tucked away on backstreets. Souvenir shops too — I liked the leftover items no one bought, not the shiny new ones.

"I preferred mid-century houses and American films set in southern places. Not westerns, but contemporary films from the ’60s and early ’70s, with those cars, that atmosphere."

SS: So even back then, you were already drawn to things with history, to nostalgia.

HN: Exactly. When I first went to Los Angeles in 1973, the city already had many older buildings. I bought a lot of prints and images of those places.

SS: And your love of mid-century design came from around that time too?

HN: Yes. At first I was into Corbusier-style interiors when I started working. But once that trend spread everywhere — in fashion offices, everywhere — I grew tired of it. Instead, I preferred mid-century houses and American films set in southern places. Not westerns, but contemporary films from the ’60s and early ’70s, with those cars, that atmosphere. Never the brand-new.

SS: You were born in 1947, so the era just after your birth was what stayed with you.

HN: Right. More the ’60s than the ’50s. The ’50s was too much rock ’n’ roll. What resonated with me was the balance of mid-century buildings, books, and magazines. Back then in Tokyo you could even find those mid-century books cheap, because no one was collecting them. That’s where I drew my references.

SS: Your Villa Bianca studio — that building was already old when you moved in, wasn’t it?

HN: Yes, it dated back to around the Tokyo Olympics. I discovered it walking between Sendagaya and Harajuku when I was working for my uncle’s design office. Later, when I became successful, I bought it. I gutted the apartment, turned it into one large loft-style studio — influenced by what I saw in New York in the ’70s.

SS: So much of your work was shaped after you came to Tokyo.

HN: Completely. Growing up in the countryside there was nothing — no art beyond high school classes. In Tokyo, and especially after traveling to America in 1973, I was overwhelmed by the influence. That trip lasted about 40 days. I remember stepping out of San Francisco airport — the sunlight, the parked cars casting jet-black shadows — it was exactly like the kind of scenes I would later paint.

SS: Were those travels the main reference for your work?

HN: The travels left impressions, but I never used them directly as source material. My actual references came from books, photo collections, interior magazines, postcards. Otherwise the painting becomes too much about personal memory.

"I was first drawn to surrealism, then American pop art. "

SS: Still, your works feel cinematic — influenced by surrealism, pop art, yet quieter.

HN: I was first drawn to surrealism, then American pop art. Surrealism was too dark, pop art more cheerful. My own work mixes both — the landscape itself is quiet, almost dark, but with strong sunlight that makes it bright.

SS: That silence, the absence of people — it’s very present in your paintings.

HN: Yes. It wasn’t something I consciously decided. Critics pointed it out later. If you add figures, the scene starts telling a specific story, and the painting becomes like a cartoon. Without people, the space stays open, more universal. And yes, it avoids issues like race — if I painted someone Asian, the viewer would place it in Asia. I preferred a landscape that anyone could see themselves in.

SS: Your works are architectural yet emotional — quiet pools, endless skies, modern buildings. Are they memories, metaphors, or imagined spaces?

HN: Imagination. I reconstruct them, combining elements. I used to measure carefully — how high the horizon should be, how wide the sky. Later, as canvases got larger, it became more instinctive. It’s about balance, distance, depth. Not anyone’s influence — just my own sense of harmony.

HN: Not at all. City pop came to me — musicians approached me for covers. If I had adjusted my paintings to fit the music, they would have become tacky. As for music while painting, I rarely play records — too much trouble. Sometimes the radio, but that’s it.

SS: Lately, vaporwave and retro-futurism scenes reference your early work. How do you feel about younger digital generations influenced by you?

HN: To be honest, I don’t see many who do it well. Some imitate surface motifs, but not with real skill. If someone truly good came along, it might even frighten me.

"City pop came to me — musicians approached me for covers."

SS: For your European audience — what kind of experience would you like them to have with your works?

HN: It’s not for me to decide. Viewers bring their own feelings. Many say my work feels nostalgic, even Americans. If it makes people feel good, that’s enough.

SS: One last question. There’s a work many people love — often described as especially quiet, poetic, introspective. Could you tell us about it?

HN: That one came from looking at a floral wallpaper in an interior magazine. I thought: what if that pattern existed outside, on a terrace wall? So I painted it. Not everything has deep meaning. I’m not a novelist — my paintings are landscapes of “what if.” Scenes I wish existed. A palm tree leaning just so, a clean simple building under strong light. Places that might not exist in reality, but should.

SS: That sense of “I wish this place existed” resonates universally — whether in Japan, America, or Europe.

HN: Yes. That’s enough for me.

Composed with cinematic precision and bathed in perfectly balanced, luminous colours, his scenes have become timeless icons of japanese pop culture and collective visual memory.